Letter to My Younger Self

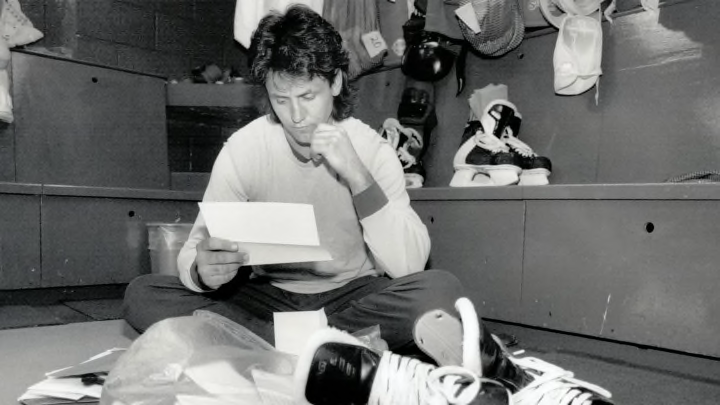

Dear 13-year-old Doug,

Writing you here from the future. It’s 2016. Still cold as hell in Ontario. No flying cars yet. They have these things called protein shakes though. They’re delicious. They even have a cookies-and-cream flavor.

You’re stuck with the cans of Ensure.

I can see you cringing, man. That weird powdered vanilla out of the tin can. Tastes like chalk. Dad makes you drink two cans a day because you’re 5-foot-2, 105 pounds, and you know damn well that Bobby Orr is 6-feet, 200 pounds.

The only way to get there is to chug Ensure and pray for a growth spurt. It’s brutal.

So learn to repeat this over and over, like your own little mantra:

He’s just too small.

Oh yeah? F— you.

He’s just too small.

Oh yeah? F— you.

I mean, say it to yourself. Don’t curse around your mother. Or your father. Or your brother. Or your older sister. They all work for the Kingston Penitentiary system, and will have no problem putting you in the penalty box. In the future, you’re going to meet somebody just like them. His name is Pat Burns. But more on him later.

On the surface, don’t curse. Just keep smiling. But repeat this mantra to yourself over and over when you don’t make the Junior A team next year.

Repeat it when your house hockey team loses, and you have to clear the ice for the next game with a huge bucket of hot water and a shovel because the rink doesn’t have a Zamboni.

Repeat it when you run hills for your cardio.

Repeat it when you finally make Junior A, and they strip you down to your jock strap and make you weigh in.

Repeat it when you stuff two pounds of quarters into your jock before the weigh in. Just don’t jingle when you walk to the scale.

Repeat it when you finish fifth in the Ontario Hockey League in points, only to get drafted in the seventh round by the Blues.

Repeat it when you return to your junior team, set the record for points in a season, and St. Louis doesn’t offer you a contract coming into camp.

He’s just too small.

Oh yeah? F— you.

Carry that chip on your shoulder forever. Because you’re going to need it to survive. Let’s talk about what happens when St. Louis leaves you hanging for a contract. Because things are going to get weird.

This isn’t going to be like the movies. When you finish your junior career in 1983, the Blues are going to be in the midst of an ownership crisis. The rumors are that they’re moving to Saskatoon. (Yeah, Saskatoon. The ’80s are going to be a strange time, kid. Just roll with it.)

So anyway, the Blues are going to leave you hanging. You’re going to hear in the media that you’re too small to compete in the NHL. When training camp opens in August, you’re going to do the only thing you can do. You’re going to get on a plane to go play in Dusseldorf, Germany.

Yeah, Cold War Germany. 1983. German Professional Hockey.

Just like you imagined it as a kid, right?

I don’t even want to spoil how weird this is going to be, but two tips here:

Memorize this phrase: Drei pilsner, bitte!

When they introduce you to the fans for the first time in Dusseldorf, there’s going to be strobe lights and crazy music and they’re going to make you skate out with a puck in one hand and a red rose in the other. Then you’re supposed to flip the puck over the glass to the fans, bend down and kiss a lady on the cheek and give her the rose.

Then some guys are going to spray-paint your name on the ice and the fans are going to go crazy.

Again, it’s the ’80s. Just roll with it. To give you some perspective, in Germany when you land.

Anyway, don’t sweat this time in your life. After a month, your agent will call you and say, “Get home.”

The Blues aren’t moving to Saskatoon. They have new ownership. They’re staying in St. Louis, and so are you. But not how you probably imagine. As insane as this sounds — and I’m sure it couldn’t sound any more insane to you as a 105-pound kid — the Blues don’t want you for your skill.

You’re going to sit down with your new coach Jacques Demers, and he’s going to say this to you:

“Doug, if you want to make this team you gotta be able to check. I don’t care if we’re playing Marcel Dionne or Wayne Gretzky. If he’s going to the bathroom, you’re going with him. Follow him everywhere.”

This statement is going to change your career. You’re not going to understand it at the time (you’re still only 155 pounds your rookie year), but you’re about to learn what it means to be an NHL player.

I’m trying to think of a way to explain the league you’ll step into as a naive kid. Let me put it in terms you’ll understand: Playing in the NHL in the ’80s is like waterskiing behind a 10-horse engine. Half the time, you’re just holding on for dear life.

What’s a penalty? Who knows. Don’t even worry about penalties. Treat them like a miracle.

Your job is to match up against the best players in the world. If they score on you a lot, you’re going to lose your job. This will be made very clear to you.

When you play against the four-time defending Stanley Cup champion New York Islanders for the first time, you’re going to be matched up against a line of …

(You ready, kid?)

Clark Gillies.

Bryan Trottier.

Mike Bossy.

Calm down. Drink an Ensure. You’re gonna be fine.

And definitely listen to your roommate, Brian Sutter, when he pulls you aside and gives you some valuable advice before the game:

“Listen to me. Whatever you do out there, do not — do not! — wake up Gillies. Leave the sleeping giant alone. Don’t get in his face. Because if you do, we’re screwed.”

See, checking against the best isn’t about who skates the hardest. It’s more mental than anything. You have to know what your opponents respond to.

You are going to have to become a little bit of a psycho out there. At your size, you are going have to make your opponent think, Jesus, maybe this guy’s not all there.

You’ll adopt a certain wild-eyed stare.

This will inspire a nickname, actually. I don’t want to scare you, but the guys are going to start calling you “Charlie.”

This is short for Charles Manson. You’ll still be a skinny little rat with a mullet. It fits.

Eventually, they’ll just call you “Killer.”

Against some guys, you’re going to whack them in the back of the calf every chance you get. In the first period, it’s going to be a joke to them. It’s not going to hurt. By the second period, it’s going to be annoying. By the third period, that calf is going to shut down.

It’s the little things.

But the calf trick doesn’t work on everyone. Some guys get charged up when you do that. Some guys, you just want to leave alone. Leave Gillies alone, or you’re going to be sorry.

Do you want to talk about the #99 kid?

You already know about him. He’s tearing up juniors right now. Watch this guy. Learn everything you can from how he sees the game. How he manipulates space. How he hides the puck behind the net. How he draws defenders to him — not just one, but two or three — to free up a teammate.

You’re going to see a lot of Gretzky.

Early on in your career in St. Louis, Gretz and the Oilers are going to come to town. Luckily, it’s around the holidays and they’ll have had a little party the night before. Going into the third, you’ll be up 5–2, dominating.

Then they’ll wake up and decide to play for real.

Gretzky will spin on you once. Spin on you twice. The third time he spins, you’ll fall right on your ass and he’ll be off to the races.

They’ll win 6–5.

Welcome to greatness.

Your five years in St. Louis, you’re going to learn the difference between being good and being great. You’re going to learn that you’re not nearly as mentally prepared as you need to be to achieve greatness.

Then you’re going to get traded to Calgary in ’88.

Al MacInnis. Lanny McDonald. Joe Mullen. The locker room will be stacked with incredible guys.

I don’t want to spoil too much of that ride for you. Until you experience it, you’ll never understand anyway.

But two things:

First. I know you love baseball. Well, keep practicing your swing. It’s going to come in handy. Because in the ’89 Stanley Cup finals (yes, seriously), you’re going to be playing a damn good goalie named Patrick Roy. He’s going to stop everything on the first shot. In a close Game 6, you’re going to get a backhand chance on him.

He’ll stop it, of course, but the rebound will pop up into the air.

Bat that sucker in.

It’ll end up being the series-winning goal.

When all your teammates line up to lift the Stanley Cup, look at their faces, especially Lanny’s. Look at the crowd at the Montreal Forum, sticking around to give your team a standing ovation. Appreciate this moment. Stand in the back of the line. You’re the new guy, after all. But be sure to actually lift the Cup while you’re on the ice, you idiot. That’s what you’re supposed to do.

Second. Tell the equipment manager to buy more beer. Way, way more beer. By the time you finish celebrating in the locker room and you get on the team plane back to Calgary, the beer will have completely run out before takeoff. You’ll turn to anything you can find.

In the span of four years, you’re going to go from ecstasy to misery in Calgary. You’ll find out what it’s like to live out your childhood dream, and you’ll also find out that the NHL can be a brutal business.

At the beginning of the ’91 season, you’re going to wake up in the morning at a hotel in San Jose and go to the bathroom. You’ll hear someone talking on the phone in the adjoining room. Then you’ll hear your name.

It’s your new general manager, Doug Risebrough. He’s talking about you.

Kid, flush the toilet and go back to bed. Don’t listen to what’s being said. Ignorance is bliss.

Don’t lay down on the floor with your ear to the door and listen in.

You’ve just been through an arbitration hearing with the team. You’ve been in a room with the lawyers. You know they don’t want to pay you. You know there’s animosity.

You know you and Risebrough didn’t get along when you played against one another.

What do you think he’s saying? Just go back to bed.

If you lay on the floor and listen, you’re going to hear some words that are going to really piss you off, and you’re going to do something you’ll regret.

“I want to trade Gilmour.”

You’re not going to be able to unhear those words. You’re not going to be mature enough to let it go. The next few months will be the most miserable time of your career. You’ll be waiting for the shoe to drop. At the team New Year’s party, you’ll tell your teammates what happened. You’ll tell them that you’re done.

You’ll walk out on the team. You’ll regret how this all goes down. You had a good thing going in Calgary, and it’ll all come apart. Over business.

Twenty-four hours later, you’ll get a call.

“You’re going to Toronto in a 10-player deal.”

Toronto. You’re probably wondering if the media has become friendlier there in the future. Nope. Same deal.

When you arrive, there’s going to be a lot of negativity around the team. You guys are going to stink that year. But in the summer, they’re going to bring in a new coach named Pat Burns.

You know how your dad doesn’t even have to yell at you, he just gives you that cop look, and he scares your pants off? That’s Pat.

He’s going to walk in the locker room between periods and give you that look, and you’re going to say, “O.K., coach. I know.”

But Pat is the best. He’s different from other coaches. When he arrives in Toronto that summer, he’s going to call you on the phone and tell you that he wants to meet you in person. Sit down. Have a beer. Talk.

So he’s going to give you an address. You’re going to hop in a cab. And you’re going to drive through an interesting part of town.

You’re going to meet your new coach at a … well, at a gentlemen’s establishment. Don’t tell your mother.

You’re going to sit with Pat and have many, many cold drinks and talk about what you want to accomplish together, what you want the team to be. You’re going to talk like human beings.

And when people there start to recognize you, you’re going to hop in a cab and pick up the conversation at the next joint.

This will go on for hours. After 10 beers, you will have planned out the ’93 Toronto Maple Leafs. You will have planned out how to not stink. How to win.

Pat will say, “Doug, I need you to be the best player in practice. Every day.”

And you will say, “Pat, yes. Yes. I will do that.”

And Pat will say, “If you do that, everybody else will follow.”

And you will say, “Pat, I’m not sure I can stand up.”

And you will stumble into a cab and go home.

That season will be a defining one for you. You’ll break the franchise record for points. You’ll have a great team. You’ll feel the whole city behind you. You’ll be one series away from the Stanley Cup finals.

And then you’ll run into #99.

You’ll have him on the ropes. You’ll be up 3–2 in the series. Overtime. One goal gets you a ticket to the Stanley Cup finals.

Then something is going to happen that you’re going to be asked about almost every single day for the rest of your life.

Gretzky is going to catch you in the face with a high stick. You’ll go down bleeding. You’ll think, That’s it. He’s getting tossed.

You can almost feel the finals in your grasp.

But then the referee, Kerry Fraser, will start talking to his linesmen, and you’ll already know what’s about to happen.

Fraser didn’t see it.

The linesmen saw it. But if one of them tosses Gretzky in the Great Western Forum in overtime, instead of the head referee, there will be a riot.

No penalty.

A few seconds later, #99 will score the winner and send the series to Game 7.

The single most important piece of advice I can give you in this letter is this: The call doesn’t matter. That game doesn’t matter. Don’t lose sleep over it. You’re going back to Toronto on home ice with a chance to go to the Stanley Cup finals.

It’s not Kerry Fraser’s fault. Seize the moment. Rewrite history. Don’t be a witness to greatness in Game 7. Because you’ll never get that close again. And as incredible as #99 is, you’ll never totally accept it.

Appreciate that time in Toronto, especially your time with Pat Burns. Because Pat is going to leave this world too soon. You’ll have to get used to saying goodbye to people before you’re ready. Life moves incredibly fast.

Eventually, Toronto will be a memory too.

You’ll make stops in New Jersey, Chicago, Buffalo, and Montreal (!) before it’s over, and it’ll be over before you can believe it.

You probably want to know so many things. But so much of what you learn in life cannot be written down. I can’t describe what it’s like to see the ice when you’re 30 compared to when you’re 20, or compared to when you’re 13.

I can’t describe how Gretzky or Lemieux have a way of controlling the ice like it’s a chess board.

I can’t describe the physical and mental pounding it takes to win a Stanley Cup.

I can’t describe to you what it takes to play in the NHL for 20 years.

The closest I can come is this …

When you win the Stanley Cup in ’89 and you get to the locker room, you’re going to be physically exhausted beyond what you can imagine. You’re actually just happy that it’s all over.

Then you’re going to see your dad standing there, waiting for you. You’re going to take a picture with him that you’re going to keep forever. You’re taking a drink out of the Cup, and he’s there smiling from ear to ear.

When he’s gone, you’re going to look at this picture sometimes. The memories will come flooding back. You won’t think about that season. You will think about what it took to get there.

You’ll think about the time you came home from a Saturday afternoon house hockey game where you scored three goals.

Remember?

You went to take your equipment out of the trunk of the car, and what did dad say?

“No. Leave it in there.”

You were confused, remember? And then he explained to you why.

“You didn’t work out there today. Everything came easy to you. Leave your stuff in there.”

So you played with soggy, stinky equipment the next day.

And when you came home all pissed off after a loss — when you went pointless and had to shovel the ice for the next game — you started walking into the house without getting your equipment.

What did he say?

“Hey, get back here. You worked your tail off today. That’s what I like to see. Get your stuff.”

A lot is about to happen to you, kid. Good and bad. But remember what your dad said and everything will work out O.K.

Now crumple up this letter and drink another gross Ensure. If you can’t get it down, just repeat after me:

Too small? F— you.